Could you introduce yourself and tell us a little about your career as a filmmaker?

Thierry Bonneau: After dropping out of computer studies, I entered an audiovisual school where I specialized in production and assistant directing. Who knows why, but I ended up as a Ripper and then Assistant Decorator on several French feature films… I already had some basic knowledge of post-production through my school, but I wasn’t very good at it. However, it fascinated me to be able to make little 3D videos on my own with a computer. I joined up with some friends from school in the spanKidz collective, founded in 2010 by Alban, among others. Then I went freelance and have since worked on quite a few commercials, music videos, and short films in compositing and VFX. I’d also wanted to direct for a long time, and when Alban asked me to co-write and co-direct this third Bubbleman, I didn’t hesitate for long!

Alban Gily: I, too, excelled at giving up my medical studies to devote myself to images and moving images. Initially self-taught in photography, video, and graphic design, I held various positions as assistant set designer, director, editor, stage manager, set photographer, and even actor… and then trained in various software programs. I directed and self-produced a few short films, then directed and edited music videos and documentaries. I’ve also worked as a graphic designer, art director, and production assistant on various projects. At the end of the day, it’s the editing and the artistic, technical, and technological direction that feed me on a daily basis— even more so than the story itself, in contrast to Thierry, who is much more structured than I am in this aspect of creation…

T.B: Nobody’s perfect! (laughs)

A.G: We have a lot in common outside of aperitifs, eyebrow-plucking, and rotten puns! Firstly, an interest in showing and distributing the films we make. Then there’s a pronounced taste for production, an organization that’s adapted, anticipated, and efficient, and therefore a workflow that’s as fair as possible, taking post-production into account right from the writing phase. Finally, artistic, technical, and technological directions on which we all agree. And, of course, BZ cinema.

What was the inspiration behind Bubbleman Superstar Mission El Cobra, and how did the story come to life?

T.B: Go ahead, Grandpa, you’re Bubbleman’s dad after all!

A.G: As with all episodes of Bubbleman‘s adventures, our inspiration comes mainly from current events. Mission El Cobra is the third opus in the saga. I could expand on this, perhaps another time. Here’s the link: https://vimeo.com/user46908202.

For the record, the second one, Hitler vs Frankenstein, co-directed with Julien Vray, we finished—with Thierry on compositing—at the end of summer 2017, just as Trump had begun his term as President of the United States. Mission El Cobra looks at border walls between peoples, particularly the one separating Mexico and the USA.

With Trump, the task of finishing the job was a colossal and aggressive one, and at the time, we had an image of this unbridled capitalism in the guise of a great cannibal. The media were full of images and news of people who had disappeared at the border, or of migrants who had traveled thousands of kilometers—often on foot—only to be turned away or die.

There was also this idea that the USA might be running towards its own collapse with a personality like Trump in power. The satirical short film M.A.M.O.N (Mexico, Uruguay – 2016) was a great inspiration. Much later, Trump tweeted that he was considering putting alligators on the Mexican border. Too late—we had already written our version of this cannibalistic border!

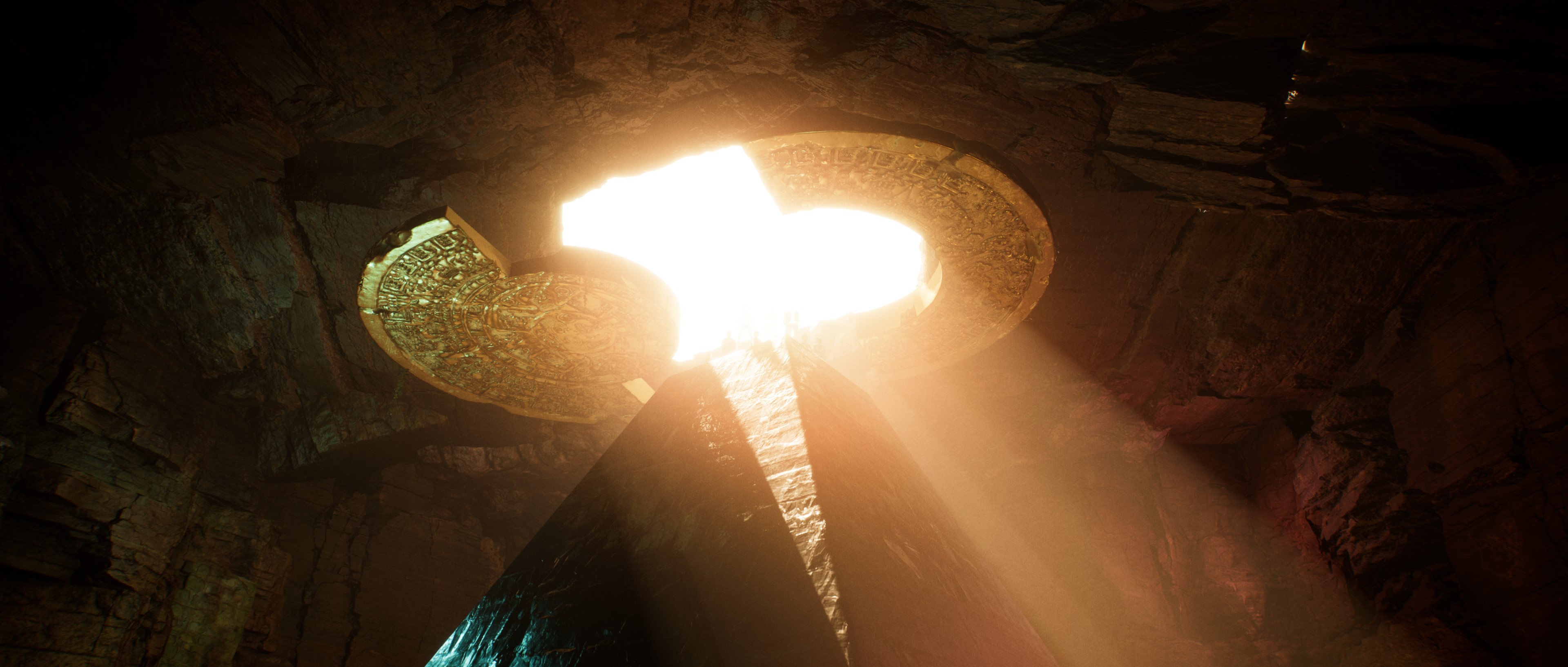

Finally, I had read somewhere in a Mayan prophecy that “everything that is buried will come to light one day.” I had enough reference points to sketch out a story seen through the prism of Bubbleman‘s dystopian universe. At the end of 2018, I pitched the project to Thierry, who agreed to co-write and co-direct this short film. As we’re also roommates, the apartment has become a veritable laboratory!

T.B: I was already familiar with the character and his zany universe. I thought it was really cool because we had a lot of freedom to write, and we could go all out with the action and the fantasy, not forgetting the humor. And then, for my first film as a director, I found animation really interesting because it allows us to do a lot of things that live action doesn’t—like a giant creature at the foot of a gigantic pyramid.

A.G: Animation allows us to get around what’s complicated in live action. For example, when there are children, meal scenes, or animals, the setup involves a certain number of difficulties. In animation, we don’t really care!

In Mission El Cobra, we placed everything that represents a live-action load. On the other hand, with UE, we can bring out all the light trucks and machinery we want. So there’s a feeling of great freedom and efficiency with this setup.

How did you approach its narrative and visual style?

A.G: The story’s structure is simple and classic, based on three acts: exposure of the villainous entity in a hostile context, presentation of the hero and his mission, fall of the hero, initiation and rebirth of the victorious hero in his new role, and finally, an unexpected finale.

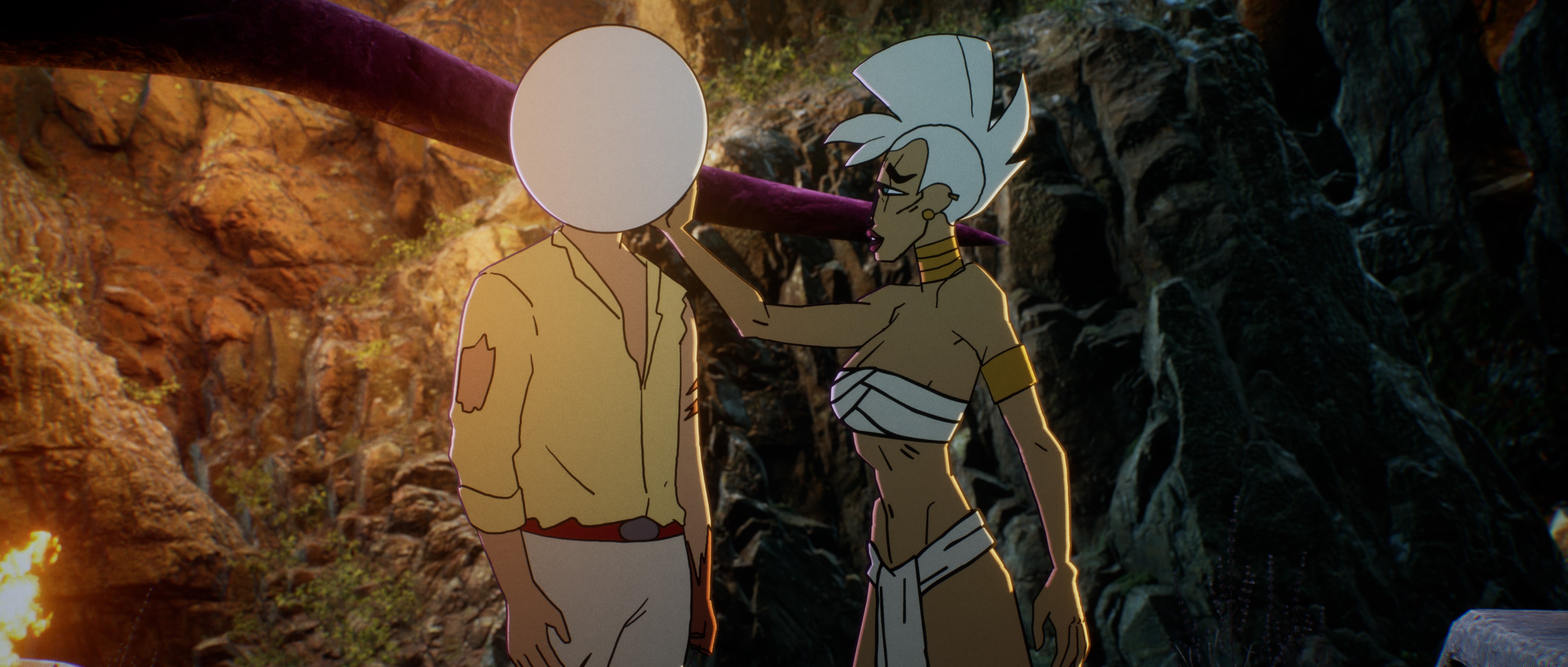

For the visual style, we based ourselves on the second episode of the Bubbleman saga: 2D animation in 3D settings. The difference is that we opted for more realistic settings inspired by video games.

T.B: What’s funny now—but much less so at the time—is that our producer, Florent Guimberteau from Melting Productions, asked us to delete half the script because it was too long and, therefore, too expensive to produce! (laughs). So we ended up with a classic three-act feature film structure, compressed into 14 minutes! Which isn’t necessarily the smartest thing to do for a short film, but after storyboarding and animating the film, we decided that it would work, with a very steady pace that doesn’t detract from understanding the story. I hope…

For the visual aspect, we had initially considered scanning models to have the sets in 3D, coupled with 2D characters, but we finally settled on Unreal Engine, which gave us total control over our sets, our atmospheres—in short, the overall artistic direction of the film.

A.G: In terms of animation, the aim was to keep a fairly steady pace, with no superfluous elements and a clear, simple structure. The staging, meanwhile, offered surprises with each sequence. Upstream of the project, there was obviously a great deal of referencing and concept artwork for the visual style.

Animation style is a key element in storytelling. Could you tell us how you came up with Bubbleman’s world and characters?

T.B: We were quite influenced by the French series Lastman, which is really superb for the clear-line, rather realistic look of the characters. That’s what mattered most to me. Alban is much better at 2D animation than I am, and what he has set up with Studio Tchak—already at work on Lastman—with its gently jerky pose-to-pose animation, seemed to me totally relevant to this project… and our finances! (laughs).

A.G: Indeed, Lastman is the benchmark. I’ve been following the work of the team behind this series for fifteen years, and I’m happy to slip in one or more quotations. The clear lines of the 2D character design and the pose-to-pose animation immediately appeared to be the most effective and relevant choices for a fast-paced adventure story. The shot values are not overly complex. There’s no real “money shot” in terms of animation.

Having said that, I wanted some dynamic animation with smears or rough drawings, all without the budget getting in the way. In reality, what I was asking the animators to do was natural and legible in the staging. Once again, the clear line and simplified costumes offered the possibility of these variations at no extra cost or difficulty.

As for the sets, some were modeled in 3D by our team, while others were assembled directly in Unreal Engine. Most of the 3D props also came from Epic Games’ marketplace, now called Fab. 2D props and FX were produced by our team’s graphic designers. Thierry animated the 3D vehicles by hand, i.e., key by key. He also did the compositing in Unreal Engine, while I took care of the 2D FX and set up the cartoon sequence at the start, in the television. Thierry then handled the final compositing in After Effects.

I had to work on three planes and other graphic tinkering to energize some of the action… In my opinion, the mix of techniques works well, serving the story and the rhythm.

What themes or messages did you want to convey with this short film?

T.B: There’s a very current and serious social context—TRUMP and his US/Mexico border wall—but above all, we wanted to make an edgy, fun, and generous film. It’s the kind of big BZ you don’t see much of in France. If it had a moral, I’d say that once you’ve rid yourself of tyranny, the grass might not be any greener elsewhere.

Can you tell us more about the technical and technological choices you made during production, particularly given the challenges of working on a very limited budget?

T.B: Yes, we had to face a lot of setbacks to finance this film. We had the support of the CNC (the French public film funding body) at first, then nothing. Similarly, we only had one region to finance the project, which is very little indeed, especially for an animated film… So we opted for a fairly simple cut to facilitate the animation and used Unreal Engine for the 3D part, as it includes a lot of free 3D assets, among other things.

A.G: Yes, a succession of setbacks and constraints led us to optimize the workflow in pre-production. Let me come back to these setbacks.

First of all, we were lucky enough to obtain this coveted public aid for starting up a project in France, called aide aux auteurs (“author’s aid”), and then, when we went before the more technical commissions—aide au développement(“development aid”), aide à la création visuelle (“visual and sound creation aid”), and aide aux nouvelles techniques d’animation et effets visuels (“aid for new animation techniques and visual effects”)—we got nothing!

This is rather incoherent from the point of view of the use of new technologies since we clearly explained that it wasn’t a question of “simple” 2D-3D integration, but that UE allowed us to manage our lights and therefore our shadows, thus resolving one of the first questions that comes up when doing 2D animation: Do we play with shadows? Yes, no, how?

At the same time, we applied for regional grants, which, when we get them, enable us to work with studios previously set up locally, outside Paris. The result was… nothing. We were called sexist, an underlying racist—the only thing missing was a pedophile accusation! We even had the most conventional argument of all: “A 15-minute animated short with so many sets and characters is unfeasible.”

Clearly, the script wasn’t to their liking. As a result, the film is here and doing well at festivals around the world.

What were the biggest creative or technical challenges you faced during production?

T.B: I’d say the most complicated challenge was to set up a viable workflow for integrating 2D characters into our 3D sets. This is something that has rarely, if ever (?), been done on Unreal Engine. I had to do a lot of integration and rendering tests to make sure it worked for all the shots.

A.G: This level of 2D-3D integration in UE has never been achieved before. Epic Games backed ten projects for the 2022 FICG, two of which were heading in this direction, but they were, without malice, bullshit.

Time was of the essence when it came to finalizing the short films, given the tight deadline between the call for projects and the festival submissions. As a result, the lighting work impacting the 2D animations and the resulting projected shadows on the 3D sets was not completed.

Could you describe a memorable moment in the production process, something you found particularly gratifying or unexpected?

T.B: Without hesitation, I’d say the sound. The sound design, the vocals, the mixing… We were superbly supported by Studio Titra, who were in charge of all that and who enabled us to work with some really exceptional French dubbers.

A.G: For me, every moment is interesting and gripping, whether alone or as part of a team—even those that could be described as boring or at least repetitive. It’s always gratifying to work over and over again, layer after layer, sculpting the project. And yes, the apotheosis was working with the Titra Film teams and those fabulous dubbers—it was magical!

The film has been incredibly well received, and everyone seems to have really enjoyed the project. As for us, we still talk fondly of those three incredible days at Titra.

There were other cool moments at every stage, too. I’m thinking of the work of the storyboarder, concept artist, graphic designers, and animators. I’m also thinking of our lead animator, with whom we redid a shot, or who didn’t mind working with a layout. And the buddies who came to help out… all the little things that kept making the project more and more lively, fun, and punk.

I’ll end here, because now we’re going to believe the guy who didn’t prepare a speech, but actually did, for the Oscars! And the big winner, who didn’t win much like the others, is… Giff and his band.

I won’t go into too much detail about this intense moment of musical creation in the image and these complicit encounters, because it would take a long time. No es pasa nada, and we ended with a Mexican evening!

Bubbleman has had an incredible run on the festival circuit. What was the public reaction and how did it influence the film’s distribution? And what was the most gratifying feedback?

A.G: The film was entered in a lot of festivals around the world, and indeed, the programmers with whom I’ve been in closer contact have said to me: “We’ve heard about it, this film is touring a lot.” We thought there might be an opening in this or that country or festival network.

Basically, distribution was thought out along three lines: the major film markets—with separate categories if possible (WTF, for example)—genre festivals, and festivals in Latin and Hispanic countries, with Mexico in the lead.

Over the course of the film’s festival career, we adjusted the shooting window, taking several parameters into account. The first gratifying event was the selection for the PIFFF (Paris International Fantastic Film Festival). It was our second entry, and we had been dreaming of being selected for this festival! So the PIFFF was our world premiere, at the legendary Max Linder Panorama. It was also the first time we had seen the film in theaters. What a pleasure—especially as there were no bugs.

We’re now going to try and get the film distributed on the French genre cinema platform Shadowz, which is also present in Spain.

Looking at the evolution of animation and filmmaking, including AI and new technologies, how do you see these trends impacting your future work?

T.B: That’s a very good question, and I confess I don’t know! Everything is moving so fast that it’s easy to get overwhelmed by it all. AI can do some pretty cool things for concept art or mood, but it can also freak you out.

On the other hand, all the advances in real-time 3D, with really stunning images and renderings, make me think that it’s now possible to make high-quality full 3D short films with a small team… but I could be wrong!

A.G: Animation, cinema, video games, special effects… everything evolves with technology and the people behind it. AI is also a tool, offering a language-based evolution, an evolution of the human-machine relationship—a different, rather playful, and efficient way of generating content. For us, it’s interesting in terms of pre-production.

Nevertheless, it would be more than a pity to see certain creative professions disappear, at least suddenly. So legislation seems both necessary and desirable. Ridiculous, lamentable, and scandalous things are happening at the moment, and I’m thinking of dubbers in France.

In the field of neuroscience, as in video games, I see the use of AI as an interesting way of advancing research for people with degenerative cognitive disorders. From an ecological and energy point of view, on the other hand, there will undoubtedly be other problems to solve on a planetary scale.

In terms of trends and practices, I try to be observant and project myself. For example, I follow industrial advances. I look at what schools are doing and what skills will emerge. Finally, when it comes to public funding in France, I look at who the members and chairmen of the various committees are, and for how long—i.e., when the heads of the committees are replaced.

For me, this is an indicator of trends. Of course, there’s no reason why we can’t make our own decisions without taking all this into account, but as someone who is deeply interested in constantly evolving techniques and technologies, this watch is also an opportunity to make the most of them in creative and economic terms.

Finally, self-production is not excluded; it is even encouraged and supported in certain aid and support schemes.

What’s next for Bubbleman? Are there any plans to expand the story or develop new animation projects?

A.G: For Bubbleman, we have a project for a tournament series based on some of the principles of Mission El Cobra, but the animation would be in 3D with 2D rendering in a Japanime style.

T.B: As far as I’m concerned, I’d love to make a short film using the same technique and workflow as Bubbleman Mission El Cobra, but going a little further with the sets and character animation…

As the project is a horrific fantasy tale based on a French legend, we’re going to have to fight hard to get this film made… It’s a long shot, but I’m not giving up hope!

Link Artstation – Breakdown of the project

Leave a comment